more>>More News

- National Day

- ways to integrate into Chinese style life

- Should they be in the same university with me?!!

- Chinese Ping Pang Legend: the Sun Will Never Set

- A Glance of those Funny University Associations

- mahjong----The game of a brand new sexy

- Magpie Festival

- Park Shares Zongzi for Dragon Boat Festival

- Yue Fei —— Great Hero

- Mei Lanfang——Master of Peking Opera

Architects, Experts Discuss Past and Future of Chinese Architecture

By admin on 2015-01-29

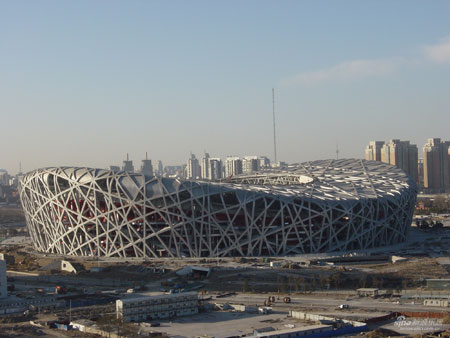

The National Stadium.

By

Hu Bei in Shanghai

Architecture is still a fledgeling

industry, whose recent successes mustn't be allowed to obscure endemic problems

of appreciation and organization. Such were the conclusions of "China

Architecture 10 Years (2000-2010): Architecture & Society," a series of

forums (held in Beijing and Shanghai, with another scheduled in Guangzhou)

inviting local architects and government officials to discuss China's past and

future relationship with architecture.

Rise of the

modern

Throughout history, China has contributed

architecure styles such as the Great Wall, the Forbidden City, the Suzhou

gardens and the Shanghai Shikumen, innovations with typically Chinese

characteristics. But where are the modern styles?

In the past 10 years,

a series of events, including the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, the 2010 Shanghai

World Expo and the 2010

Guangzhou Asian Games, have seen China's

cityscapes enjoy worldwide coverage as a modern showcase of rapidly rising,

large concrete buildings.

Nowadays, if Beijing and Shanghai are

mentioned, constructions such as the National Grand Theater, the new China

Central Television headquarters, the National Stadium (the Bird's Nest), or

Shanghai World Financial Center (until now, the highest building in the world)

and Jin Mao Tower immediately come to mind. Their common features are that they

are large, tall and modern.

At the Shanghai forum, Yang Ming, the

director of the East China Architectural Design and Research Institute, declared

that the achievements of the past 10 years are so huge that one could

effectively ignore any construction done in the first 20 years of reform and

opening-up.

"At present, when you go outside, 80 percent of the

outstanding buildings you can see in China were built during the last 10 years,"

Yang observed.

Yang pointed out that since the National Grand Theater

project was designed by French architect Paul Andreu and began construction in

2001, more and more domestic construction projects in China have opened their

doors to foreign architects and Sino-foreign cooperations are rapidly emerging

here. "It is really a very good opportunity for the future of Chinese

architecture," Yang said.

Suzhou garden. Photos:

CFP

Big

is better

Most of the architects and experts involved in

the forums agreed with the analysis and thought that the recent success was

closely related to events in China during this time.

According to Hu

Yue, director of the Beijing Institute of Architectural Design and Research,

there is a correlation, unique in China, that when grand events take place,

large buildings always appear.

"Throughout the history of world

architecture, large buildings were not always related to big events," Hu said,

"Of course, China has the largest population in the world, with plenty of

reasons for big buildings, but whether it's necessary or worthy to invest so

much human and material resources into them is worthy of

consideration."

Hu wondered, "What on earth is good architecture?" In his

opinion, there seemed to be two criteria in China for judging.

"One is

from the government and is the 'official' one, which usually thinks that 'large'

and 'important' symbolic buildings are good …The other is repressing the public

and the media, who seem always to have the opposite view and judgment to the

official criterion," said Hu.

Zhuang Weimin, director of the

Architectural Design and Research Institute of Tsinghua University, expressed

his helplessness as an architect when facing this "offical" dilemma. In order to

meet the deadlines of large events like the Olympic Games and the World Expo, he

said, of design projects always have to be finished within a very short time.

"The years of working experience of the architect cannot be well-matched with

the design and the construction. We are always pitched into designing," he

complained.

"Moreover, once finished, are there any [buildings] that

really have architects' own care and thought inside? I'm not

sure."

Shanghai

Shikumen. Photos: CFP

Duty

of an architect

For critic Wang Mingxian in Beijing, the

problem was different. Although he conceded the foreign and Chinese success of

the last decade, in Wang's opinion, "this period has not raised a mature,

worldly, influential and contemporary Chinese architecture team. [Their] force

is dispersed and scattered."

Yu Ting, a Shanghai architect, and Sun

Jiwei, head of Jiading district, had their own views. Yu pointed out that

procedures and approvals beyond the ability of architects have always been

needed in China. Yu thought that, for most of the time, it is enough that an

architect carefully finish the task.

Sun disagreed, stating that

architects had a different duty. "They must learn how to examine their own

problems," Sun said. "As long as the architect really has his own personal

pursuits and ideals, the government will always need and support

them.

"Not just something unconventional," he further explained. "But

[someone who] can really supply good, especially environmental friendly, designs

with limited resources – not very avant-garde or conceptual – but requiring a

large amount of human and financial resources."

As Wang said at the very

beginning, the past 10 years may have been brilliant for Chinese architecture

but have also produced the most problems. These are ones not only architects,

but also everyone involved in Chinese architecture, need to think about and

consider deeply.

- Contact Us

-

Tel:

0086-571-88165708

0086-571-88165512E-mail:

admission@cuecc.com

- About Us

- Who We Are What we do Why CUECC How to Apply

- Address

- Study in China TESOL in China

Hangzhou Jiaoyu Science and Technology Co.LTD.

Copyright 2003-2024, All rights reserved

Chinese

Chinese

English

English

Korean

Korean

Japanese

Japanese

French

French

Russian

Russian

Vietnamese

Vietnamese