| Home > Living In China |

Tea, The Quintessential Chinese Beverage

Tea is an elixir. It invigorates, offers warmth, is calorie-free, has less caffeine per cup than coffee, and is the national drink of more than one country. Tea is also society, agriculture, and history. Above all, tea is quintessentially Chinese.

Imagine olden days when traders trekked across Asia and the Arab world, the caravans beating gongs, and hoisting flags heralding drivers of different nationalities. Turkish traders reached northern borders of China to buy their chay, a China flatlands and Cantonese pronunciation, while others of other nationalities made it to Fujian to buy tay, as the Chinese in that region called this beverage. Over mountains and rain forests, they plied the ancient caravan routes while tasting, sip by sip, to deliver this exciting new commodity, China's national drink.

When tea came to Europe, particularly France and Holland, it provoked a war of words over supposed curative properties; perhaps, that is why it never stood a chance to match coffee's popularity on the continent. However, in England, this beverage made major inroads; it was even advertised frequently in newspapers as early as 1658. As a beverage, tea reigned supreme, even became an all-curing elixir. Thomas Garraway's shop sold it in both beverage and leaf form, and touted its use for everything from memory loss to scurvy, sleepiness to dropsy, something to provide a gentle vomit, and as an item to give the drinker heavy dreams.

Who could resist? Certainly not the Venetians who used it for their stomach troubles or their gout, or Charles II who taxed it heavily, or his wife Catherine of Braganza who thought it so valuable that she brought her own leaves from Portugal in her trousseau. Not even the East India Company, who in 1689 began to import it regularly to Holland, England, France, and beyond, could resist; why should they as they were given a monopoly on the tea trade until 1833.

In America, tea evokes other memories. Among them, the Boston Tea Party, and the psychological and pharmacological effects of tea and toast. For centuries, tea captured and drew lovers to this splendid drink with elegant tea times and more elegant tea cakes.

Most recently, tea has caught everyone's attention as a subject of cancer research. A strong relationship has been found between green tea and animals, a weaker one with man. Dr. Gao and his colleagues reported in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute in Volume 86(11) on pages 855-8 in 1994, that a reduced number of cases of esophageal cancer was related to an increased consumption of green tea. Thus, in the 1990's, tea was xanadu.

Tea, an infusion of the leaves of an evergreen, is the world's most widely consumed beverage, about twenty percent consumed green, mostly in Asian countries, and eighty percent black, as enjoyed in the western world. Exotic teas are profitable and proliferating. Tea parties are once again in fashion. Writing about it is derigueur, its history, geography, brewing methods, salubrations, and delicacies to accompany it important things to know about. Research about tea is as exciting as the varieties sold.

Knowledge about the origins of this ancient beverage is scanty. Perhaps drinking it began by a descendent of one of the twelve Emperors of Heaven. Maybe it was introduced later by a scholar returning to China from abroad. A non-Chinese myth relates that Bodhiharma, a Buddhist saint, fell asleep while praying. Furious at himself, he cut off his eyelids and threw them down whereupon, they took root. Overnight, they grew into a tea bush, and voila!

The most popular Chinese version of the origins of tea is that the beverage was born in the year 2737 BCE. Some say it was at a reception for, others think by, or in the garden of Emperor Shen Nung, one of the first physicians in Chinese history. The tale tells that leaves from an evergreen shrub accidentally fell into a pot of water servants used to make his regal boiled water; even then they knew not to drink unboiled water. The Emperor approved the flavor, deduced it had medicinal powers, and prescribed it to perk up people.

Soon thereafter, tea was appreciated by all. It was so valuable in the sixth century, that it was pressed into cakes, some used as currency complete with imprints, emblems, and a variety of designs. Later, in the Tang Dynasty, the poet Lu Yu, born in the second quarter of the eighth century, wrote a classic volume called Ch'a Ching. His Book of Tea documented every aspect of growing, processing, and preparing tea. It even codified how to think about tea--elevating it to an art form.

During the Song Dynasty, very elaborate ceremonies were developed for tea (green only), using a dried ground and whisked form to be drunk from a special bowl. In the fifteenth century, during the Ming Dynasty, using whole leaves and making tea in pots became fashionable. Teacups replaced bowls as the vessels of choice. It was this method of tea preparation and this type of tea that Dutch traders found and imported to Europe, the year 1610. Later the British East India Company took over the bulk of the trade becoming what we might consider a tea cartel.

Where or when aside, all leaves of real tea come from a tropical bush: Camellia sinesis, native to China, Tibet, and India. Now grown further afield, tea exporting countries are: China, Sri Lanka, India, Kenya, Indonesia, Argentina, Malawi, Bangladesh, Zimbabwe, and Vietnam. The major importers of tea are the United Kingdom, Russia, United States, Egypt, Japan, Morocco, Australia, Germany, and Canada; in declining order.

No matter the location, the leaves of this evergreen are picked, allowed to wither a bit, then heated. Some call the process frying, others fermenting, still others are more technically correct and refer to it as oxidizing. This multi-named singular set of processes gives tea its characteristic color and taste and produces what the Chinese call green, oolong, or red teas. In addition to color, the qualities of the teas are differentiated by the season the leaves are picked, whether what was collected was bud and first leaves or larger ones, and where they were grown, elevation a critical item, and three thousand to six thousand feet for the finest. The western world knows tea not by the color of the brew but by that of the leaf, so we call these color variations green for that which is unfermented, oolong for the semi-fermented, fried or oxidized, and black for those leaves that are fermented or oxidized.

Tea at one time was picked mostly by women; hand picking the leaves still produces the best and most expensive tea, lower qualities are now picked by machine. When collecting leaves for Tung Ting or Dragon Well Tea, only the end two leaves and the bud will do, and a pound of the finished product takes a whole days effort. No wonder it not only is the best but can be the costliest. They say that to 'delight in picking the young leaves for three days before the Qing Ming festival is a treasure, three days after it is trash.'

For the record, English and Indian teas are better known by the size and shape of their leaves, the meanings of orange pekoe and pekoe, and by their blending of teas and other ingredients such as in Earl Gray and English Breakfast teas. The tea bag has recorded origins early in the Sung Dynasty (960 - 1279 CE) and then was a silken gauze bag. New York merchants later used that idea of tea bags when they gave out free samples but tea and tea bags didn't really become popular until Arthur Godfrey popularized Lipton's on both radio and TV.

Tea drinking in China has become an inextricable component of living. It is honored as one of the seven necessities of daily life making it more than just an item for quenching thirst. It is a ritual and a means of communicating, welcoming, and showing respect.

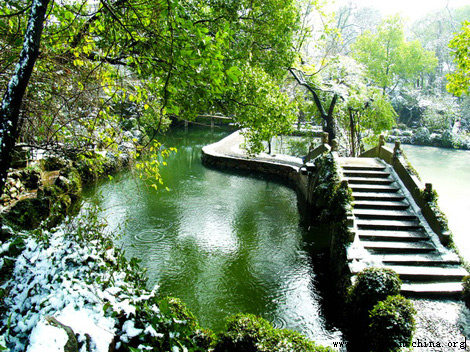

Though Chinese tea rituals vary by region and ethnicity, each and every one of them is a means to contemplate, commemorate heroes and ancestors, and a time to enjoy a fine brew. Rituals frequently include music, incense, flowers, fruits, and special verses. They can be for appreciating nature and life.

Among the Han, the major ethnic Chinese population (who are more than ninety-two percent of all Chinese), there are many tea rituals. One is a four seasons formality meant to recapture the spirit and wonders of nature. Representing the harmony of the four directions, east--west--south--north, with the five elements, gold--wood--water--fire--earth, and matching colors of cloths, flowers and tea sets, special guests are invited to taste four different teas.

Custom

more

moreWeb Dictionary

Primary&secondary

Beijing National Day School

Beijing Concord College of Sino-Canada

Brief Introduction of BCCSC Established in the year 1993, Huijia School is a K-12 boarding priva...Beijing Huijia Private School

print

print  email

email  Favorite

Favorite  Transtlate

Transtlate